How Race And Politics Created Two Different Americas For Cubans And Haitians

Cuban and Haitian Americans have formed a fundamental part of South Florida’s culture since the mid-20th century.

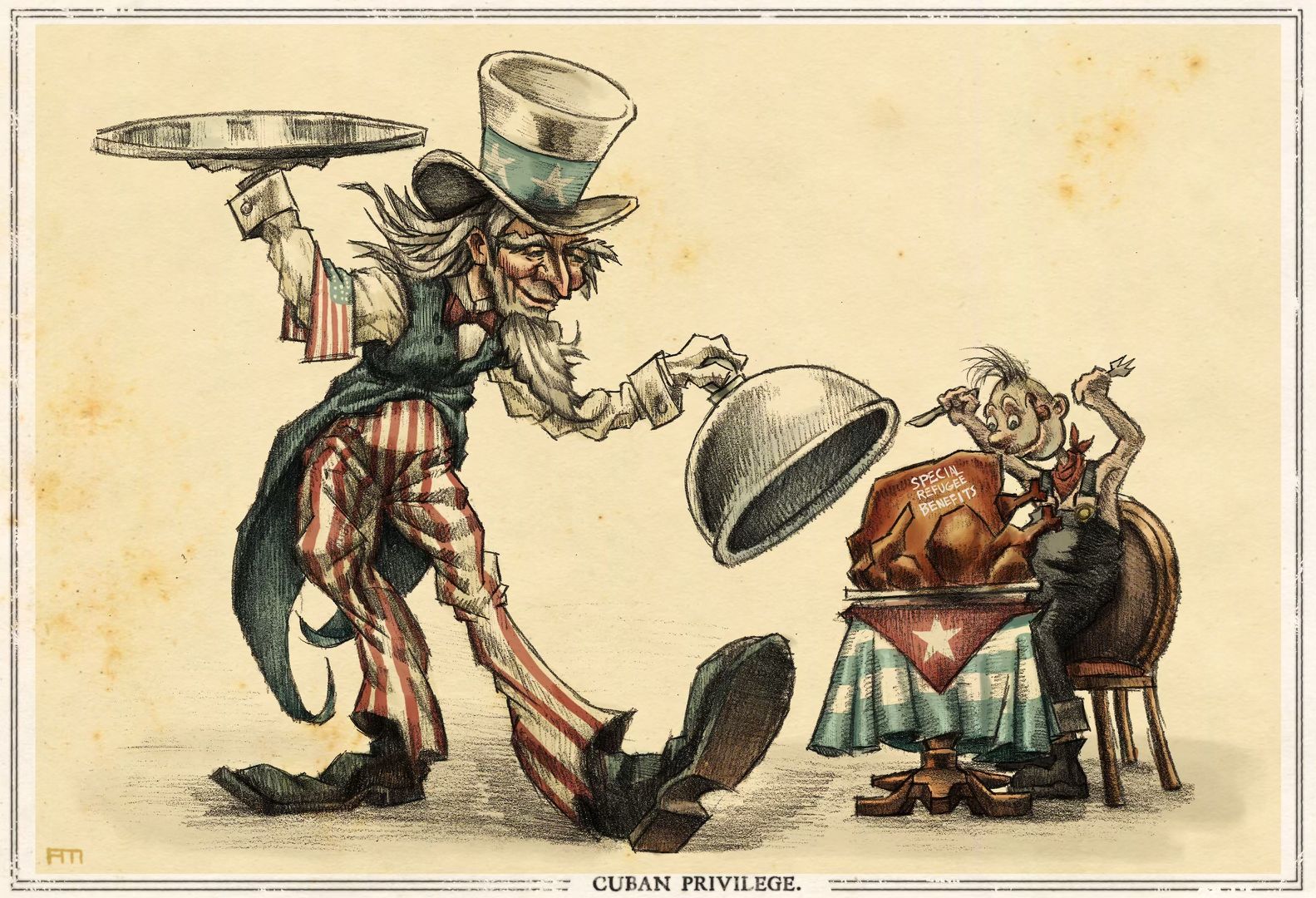

However, both groups face vastly unequal outcomes once they reach the land of opportunity due to an immigration policy that disproportionately benefits Cubans.

Similar Stories, Different Outcomes

After Fidel Castro consolidated power in Cuba and aligned himself with the Soviet Union in 1961, the U.S. feared the spread of communism. In turn, they blockaded the island to cripple it economically.

In 1966, the Lyndon B. Johnson administration passed the Cuban Adjustment Act, which labeled Cuban immigrants as political refugees and granted them permanent residency within two years of arriving in the U.S.

Sociologist Susan Eva Eckstein notes in her book, Cuban Privilege: The Making of Immigrant Inequality in America, how Cuban exiles also received benefits like relicensing programs and supplemental security income.

However, the Cuban Adjustment Act was not a humanitarian policy.

It was an attempt to politically punish Cuba by draining it of its talent.

While the Cuban Revolution was underway, Haiti suffered from the dictatorial rule of the Duvalier dynasty from 1957 to 1986. As in Cuba, political repression and human rights violations were the norm.

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, thousands of Haitian Americans fled to the U.S. In 1980, 25,000 Haitians arrived in South Florida by boat.

But the U.S. never created a law for Haitians equivalent to the Cuban Adjustment Act.

Instead, many Haitians were considered as economic migrants rather than political refugees, denied a protected legal status and deported.

Today, Haitian-Americans in Miami are poorer, less educated, less likely to own a home and more likely to be unemployed than Cubans, according to the Racial Wealth Divide Initiative.

Fairness For All

Nowadays, it’s easy to blame individuals for their personal faults. If you are poor, it’s because you are lazy or stupid.

This perspective fails to acknowledge how sociopolitical structures affect our lives and contributes to racism in America.

If there’s one thing the Cuban Adjustment Act has proven, it’s that with enough help, a refugee coming from one of the poorest and most oppressive nations can reach the American Dream.

Rather than end the benefits to Cuban Americans, the U.S. should seek to expand them to other refugees.

All refugees, not just Cubans, are worthy of reaching the mountaintop.

Juan S. Gomez is a junior at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina majoring in sociology. He served as editor-in-chief of The Reporter during the 2022-23 school year.