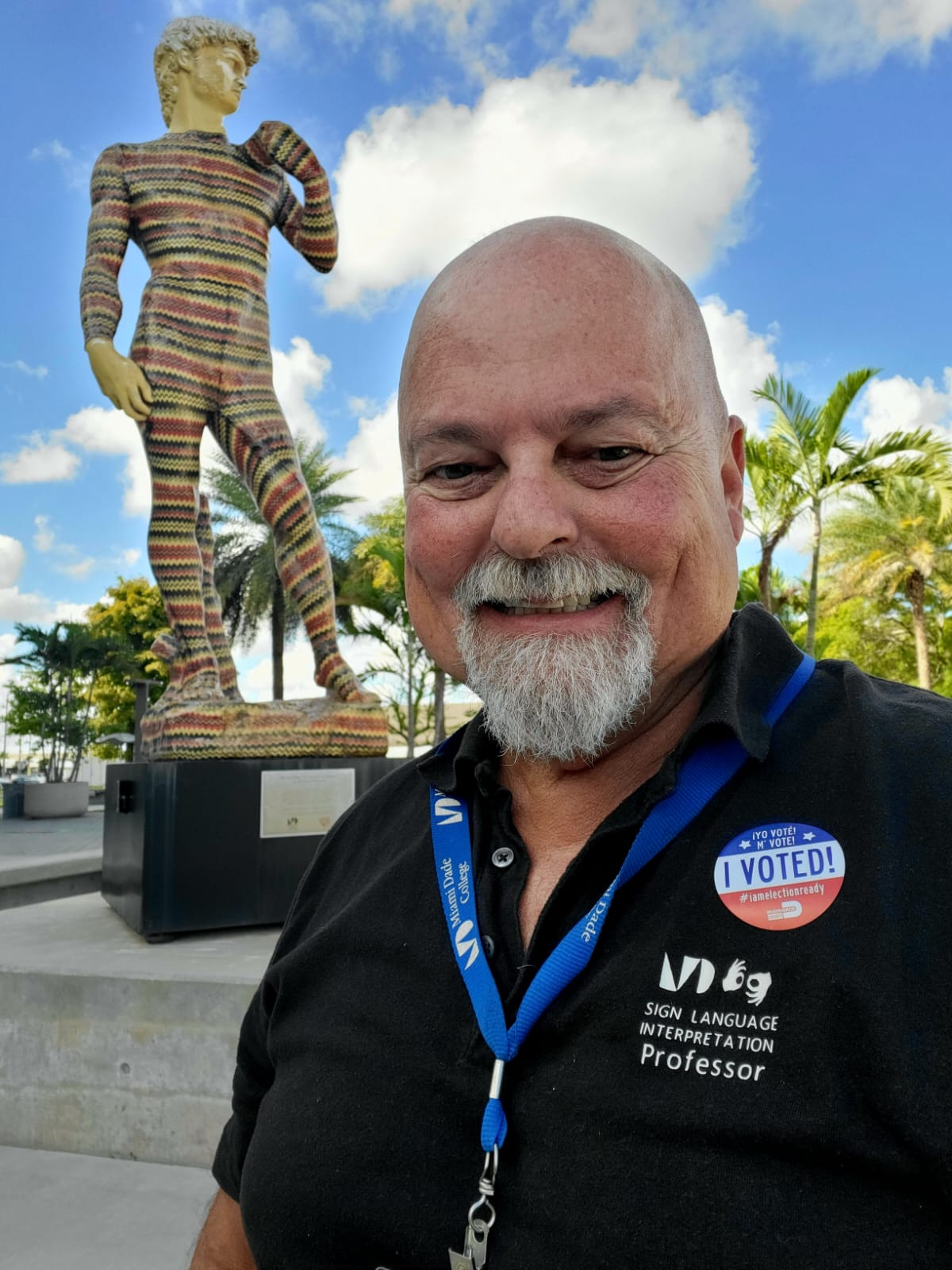

North Campus Sign Language Professor Dies In Early Morning Car Accident

Jose Granda enjoyed putting a smile on his students’ faces.

The 69-year-old deaf American Sign Language professor was known for sharing personal anecdotes and showing humorous videos that illustrated the challenges sign language interpreters face.

His passion for the craft inspired those who took his classes for more than three decades at North Campus.

“He loved his students, his job and his deaf community,” said Annette Valido, who took Granda’s conversation skills and finger spelling courses in 2016 and now serves as a sign language interpreter. “He encouraged you to tell the story in ASL.”

Today, his loved ones are grieving his loss.

Granda died just after midnight on Dec. 11 after a car accident at 1700 SW 22nd Ave—he was less than a mile from his home in Coral Way.

According to NBC Miami, his Honda CR-V was struck by a tow truck, skidded 140 feet and caught on fire after it collided with a power pole.

Devoted Professor

Granda was born deaf in Havana, Cuba in October of 1953.

When he was four years old, his parents, who were divorced, fled Fidel Castro’s communist regime and relocated to Miami. By the early 1960s, Granda moved to New York.

A decade later, the teenager enrolled at the Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind. He graduated in 1973 and earned a bachelor’s degree in drama six years later from Gallaudet University—a university for the deaf and blind located in Washington D.C.

Granda started his teaching career in the 1980s, serving as an ASL professor at San Francisco State University, the University of Central Florida, Valencia College and the now-defunct Vista College in El Paso, Texas.

He returned to Miami in the early 1990s and began teaching ASL courses at North Campus, where he built a reputation as a strict but charismatic and passionate professor.

Granda arranged the seats in his classroom in the shape of a U to ensure everyone communicated strictly through sign language.

Many of his students stayed connected to him long after they had taken his class. They reunited with Granda during a bi-monthly social event he coordinated for students, colleagues and deaf interpreters at a Starbucks in Westchester.

Vanessa Marrero befriended Granda during a meet-up in 2021. At the time, she had very little sign language experience.

“I was intimidated,” Marrero said.

Despite living in Homestead, Marrero enrolled in Granda’s manual alphabet and conversational skills courses at North Campus last Fall.

“When you learn ASL it’s better learning from a deaf person,” said Marrero, who is set to complete her associate’s degree in sign language interpretation this summer. “They teach you their culture.”

Aside from teaching, Granda was also a sign language interpreter. One of his assignments was at Florida Relay—a service that facilitates over-the-phone communication for blind, deaf and speech-impaired people. The program provides a transcript of audio conversations.

“You always saw him expressing himself in a manner that [was] always heartwarming,” said Fernando Lopez, who was an interpreter at Florida Relay in the early 1990s and is now the chairperson of the English and Communications Department at North Campus. “What you saw is what you got.”

Big Heart

Granda’s love for teaching led him to speak at national conferences and deaf schools to advocate for the deaf community. Each year, he spoke at Silent Weekend—a conference in Orlando celebrating the use of sign language.

He was also part of the Deaf Hispanic Association and the Broward County Association of the Deaf.

“He just really valued sign language as a language and was an amazing support for the deaf community,” said John Paul Jebian, a deaf professor at North Campus who teaches sign language. “[Jose] was a star and a great tutor as well.”

Granda was also a leader in the gay community. In the 1980s, he taught a course on HIV/AIDS prevention and served as a member of the Rainbow Alliance of the Deaf and of the Deaf Queer Resource Center.

Last August, he attended the Deaf Queer Men Only conference in Toronto.

In addition, Granda was an avid traveler. He visited Italy, France, Cuba and The Netherlands. To fund his trips, he sold paintings depicting his passion for sign language, the Cuban flag and flamingos.

He occasionally wore clothing featuring flamingos because the bird was his favorite animal. He saw them as extravagant and glamorous.

“The last class I had with him, he was wearing a flamingo hat,” Marrero said. “He had a little Christmas ornament on it and he was so excited…It was just a small thing that made him happy.”

Granda was also a man of routine.

He commuted daily from his home in Coral Way to swim at the public pool at Shenandoah Park. When the park closed because of the pandemic, he used the pool at his sister’s house in South Miami.

During football season, Granda always ate pizza while watching Dolphins games. He also frequented local Cuban eateries like Harry’s Havana, La Carreta and Versailles to catch up with friends and family.

But his most consistent habit was his daily communication with loved ones. He texted, video-called and shared funny videos through social media.

“I’ll miss not having him text me at all times of the day,” said Maria Monti, Granda’s half-sister. “I’ll never have that again.”

To honor his legacy, the Miami Dade College Foundation is collecting money for the Jose Granda Memorial Scholarship. It will support students studying sign language.

Click here to subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter, The Hammerhead. For news tips, contact us at mdc.thereporter@gmail.com