After 31 Years In Prison, This Man Is A Semifinalist For $55,000 Scholarship

Eddie Fordham, Jr.’s future looked bleak as he sat in a suicide-watch cell at the Escambia County Jail while awaiting his death penalty trial.

Bitterness, sadness and fear welled up in the then 18-year-old’s heart.

But things changed one night, when someone slipped a letter under his door containing a message from Judge William White, Jr.

“He said…’There will be consequences to your actions. But if you will accept personal accountability for your poor decisions, you have a story to tell other youth,’” Fordham recalls.

For the next 31 years, prison would be Fordham’s home. But today, Judge White’s letter of encouragement rings true.

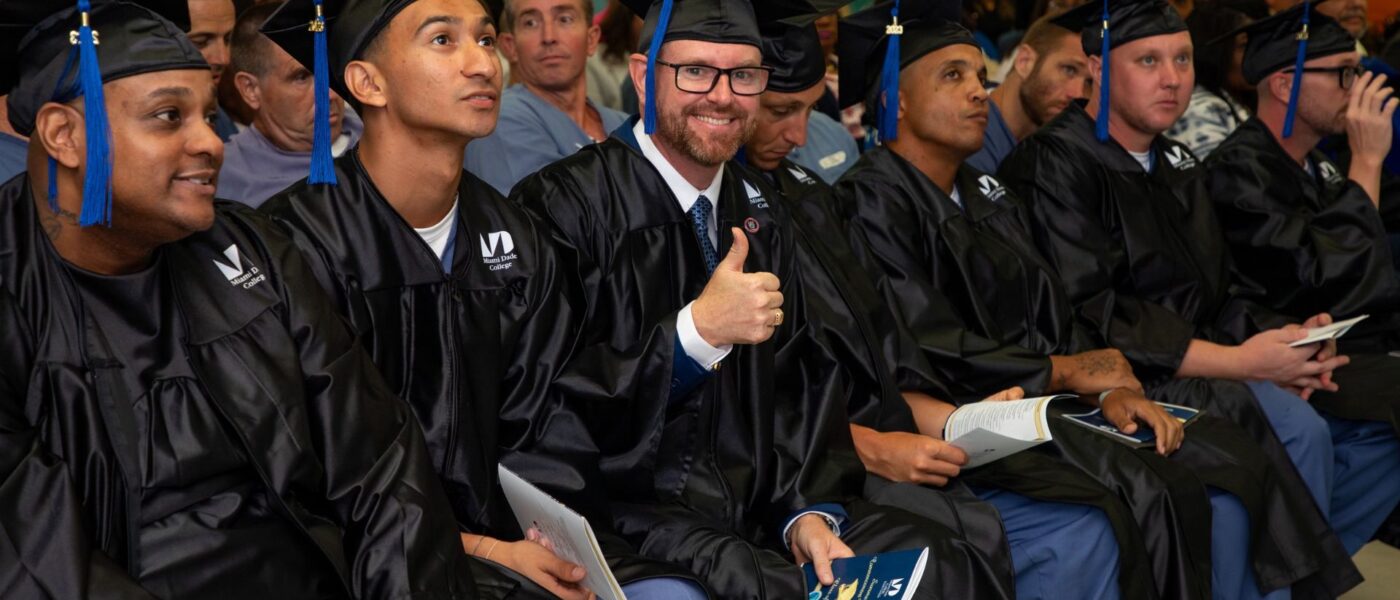

Fordham, who was released on parole in April of 2022, graduated from Miami Dade College’s College in Prison Program last summer. In March, he was tabbed a semifinalist for the Jack Kent Cooke Transfer Scholarship.

The national prize is awarded to 60 students each year. Recipients get up to $55,000 annually for living expenses, books and tuition as they pursue a bachelor’s degree.

Making Choices

Fordham, who was born Larry Edwin Fordham, Jr. in December of 1972, grew up in Pensacola. In high school, he was perceived as a “mama’s boy” and yearned for acceptance.

That sparked a domino effect of poor choices—stealing, driving recklessly, climbing balconies and hanging with the wrong people.

By his senior year, Fordham’s life took a turn for the worst when two friends asked him to drive them to an auto parts store to conduct a drug deal, he said.

What the teenager didn’t know, he says, was that his friends intended to rob the store clerk and kill him as Fordham sat outside in the driver’s seat of the get-away vehicle.

On Feb. 11, 1991, he was charged with first-degree premeditated murder, first-degree felony murder, armed robbery and grand theft.

Although he was acquitted of the first charge and spared the electric chair, Fordham was found guilty on the other counts and sentenced to life in prison.

“People tend to think that because of what happened to me, because I got arrested as a teenager or I was getting in trouble as a juvenile… that somehow I must have come from, you know, an abusive home or [had] an alcoholic parent or something like that,” Fordham said. “That wasn’t the case at all. I got into this trouble because I made the choice to get into trouble.”

“Education Was My Redemption”

After sentencing, Fordham was transferred to a rusty cell in Lake Butler, Florida.

Puddles of sewage water and roaches covered the floor. Crust lined the stainless steel toilet. Hallways were filled with inmates’ yells.

And his mind was burdened with the consequences of his actions.

Eventually, Fordham realized he was missing one course, English 4, to graduate high school.

That realization fueled the next three decades of his life.

To finish his final high school course, Fordham wrote a letter to the Escambia County Superintendent of Schools.Two years later, he became the first person inside Apalachee Correctional Institution to attain his high school diploma.

He was then transferred to Sumter Correctional Institution in Bushnell, Florida, where he joined the Responsible Inmate Taught Education (RITE) program, which trained incarcerated people to become tutors. He learned about the cognitive development of the brain, educational psychology and how to run a classroom.

Fordham committed one year to teaching at the New River Correctional Institution, one of the most dangerous correctional institutions in Florida. He taught incarcerated people to read, write and do math.

Throughout his three decades behind bars, Fordham was in 17 maximum security prisons in Florida. He led initiatives such as the Pope Literary Club and the Character Builders Gavel Club, an organization aimed at improving public speaking.

Fordham also created the Prison Impact Tour (PIT) program, an initiative that brings juvenile delinquents into prison to see the consequences of their decisions.

“We as a society, have to at least provide the tools to give people access to believe in themselves and that’s all I was doing,” Fordham said. “I’m just a guy who, for my own personal life, found that education was my redemption.”

College-Bound

Five years ago, Fordham found himself at the Everglades Correctional Institution where he participated in ESUBA, a two-semester program aimed at reversing the psychological effects of abuse. The initiative is led by Samantha Carlo, an associate professor senior at the School of Justice, and Minca Davis Brantley, a psychology professor at North Campus.

In 2021, he joined MDC’s College in Prison pilot program—a project funded by the Second Chance Pell Program, a federal initiative that helps incarcerated people attain college degrees.

But his journey to an associate’s degree was far from smooth.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, classes were held through zoom. Prisons were on 24-hour lock-down for months. No visitors were allowed. School lessons were mailed to the prison for students to work on independently and mailed back to professors.

Violence spiked.

One night, a man who was beefing with another inmate over a debt, hit the other man with a can of shaving cream and “split the guy’s head open.”

“It woke me up and when I opened my eyes, I had this man’s blood dripping on my face because he was leaning over the head of my bunk and blood was pouring over me, and that really freaked me out,” he said.

During another instance, Fordham said a man jabbed an “ice pick” into his chest over a bag of chips and coffee.

But the greatest challenge Fordham faced was the death of his father, Larry, Sr., who passed away from esophageal cancer on Feb. 24, 2021.

A Whole New World

By April of 2022, Fordham was granted parole. He was missing one course to earn his associate’s degree—Spanish 2—but lacked the financial resources to pay for it.

However, after meeting Terrell A. Blount, the director of the Formerly Incarcerated College Graduates Network, that changed.

Fordham’s situation inspired Blount to create the Removing Barriers Scholarship Program to support individuals with past convictions.

With the grant, Fordham, who transitioned to a halfway house in Tampa after being granted parole, completed the missing course in April of 2023 at Hillsborough Community College.

Last summer, he returned to MDC to graduate with his friends.

“It’s very easy for people who have been in prison to be afraid to be told no,” Blount said. “But Eddie, he doesn’t consider those things. He’s like, you know, ‘If there’s a way and if God made this possible for me, then he’s gonna allow it to happen.”

These days, Fordham is grappling to adjust to 21st century technology.

Recently, Fordham thought his brand new lap-top was broken because it displayed a “no internet” message until a friend helped him.

“He goes, ‘Oh, you need to connect to your Wi-Fi.’ And I’m like, ‘Connect to my what?’” Fordham recalls. “I thought he was saying high five or something.”

Pumping gas was also intimidating.

“I didn’t know how to make it work,” Fordham recalls. “And when I finally did get it to work, it had a TV screen that came on. And when it started playing a video, it kind of scared me because I didn’t expect a gas pump to have an entertainment system built into it.”

However, the most frustrating challenge has been finding a job. That search ended in June of 2022 when he landed a gig as an inventory associate at Feeding Tampa Bay, a non-profit organization dedicated to ending food insecurity.

“I think the best thing about Eddie is that he walked out of prison, really, without a lot of baggage and scarring. He has a very good outlook on life. He’s always wanting to help people. He’s a go-getter,” Carlo said. “You know, some people get out of prison and it’s ‘Oh, woe is me. What am I going to do now? No one’s gonna hire me’… he just has a remarkable spirit and an attitude where most people are broken down by the system.”

Fordham currently serves as coordinator of Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project, a peer mentorship program at Auburn University. His first day on the job coincided with his first day in prison 33 years ago.

If he wins the JKC scholarship, Fordham is considering schools like Auburn University and the University of Alabama. He plans to pursue a bachelor’s degree in communications and public administration.

“I know there are some very, very smart students out there—a lot younger than me, a lot smarter than me, I’m not gon’ lie. But I really hope and pray there’ll be at least one slot open,” Fordham said. “And that one slot will not just be for Eddie Fordham, but it will hold the gate open for others, so that they may see hope; so that they will pursue their college education while incarcerated. And when they get out, they will know that they, too, can apply for the Jack Kent Cooke scholarship and win it the same way that Eddie Fordham did.”

Click here to subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter, The Hammerhead. For news tips, contact us at mdc.thereporter@gmail.com.