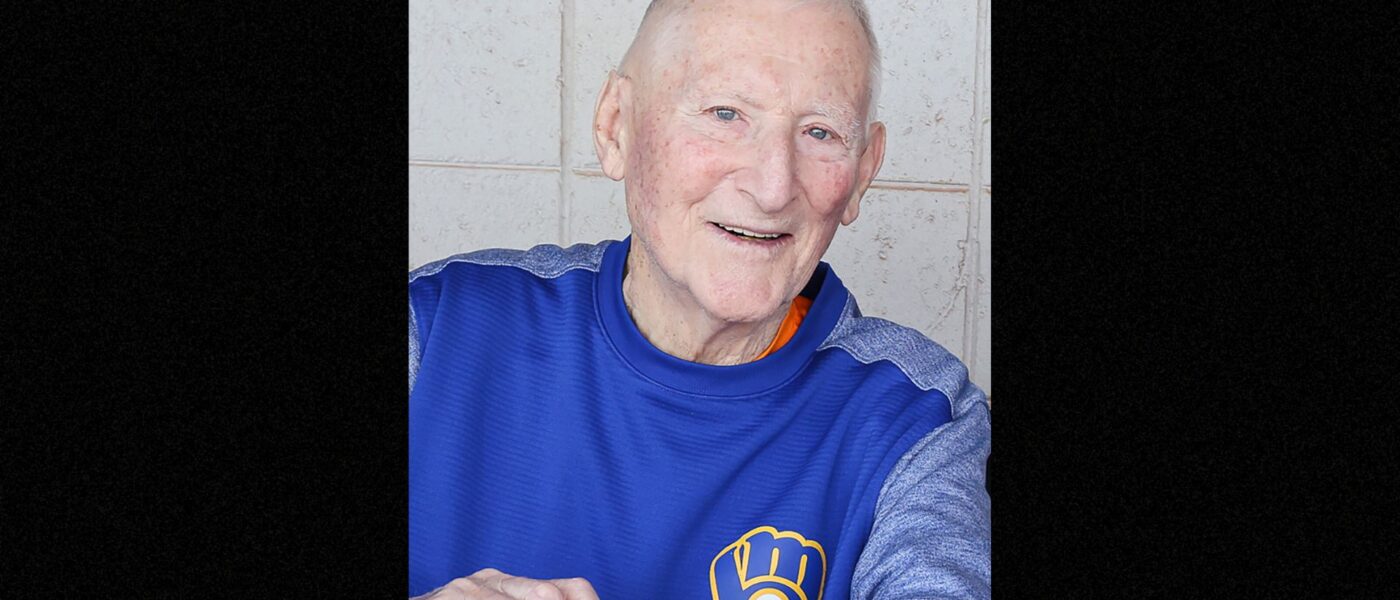

Architect Of Baseball Program At Kendall Campus Dies At 94

Baseball holds a special place in the hearts of South Floridians; it’s a symbol of national pride and community.

At Kendall Campus, the baseball diamond was Charlie Greene’s pulpit—it’s where he taught life’s lessons.

The legendary coach, who pioneered the campus’ baseball program in 1968 and oversaw it for three decades, passed away on March 13. He was 94.

Early Years

The oldest of six siblings, Greene was born in Irvington, New Jersey in 1929, the year the Great Depression started, to Rose Rainko and Patrick Joseph Greene.

He spent his early childhood traveling between Poland, his mother’s homeland, and Ireland, his father’s native land.

Greene eventually returned to the United States and discovered he had a knack for pitching at Dover Senior High School in New Hampshire.

After high school, he pitched for one season in the now defunct New York Giants minor league system, but his career was derailed after he sustained a career-ending injury to his right arm.

In 1951, Greene was drafted into the Army during the Korean War. He served in the Corps of Engineers, building bridges and digging fox holes. Two years later, he was relieved of active duty to tend to his ailing mother, who had cancer.

When he returned home, Greene attended the University of New Hampshire, where he earned his bachelor’s degree.

Shortly after, he landed a job at Portsmouth High School in New Hampshire, coaching baseball and basketball for six years, eventually earning a master’s degree from Boston University.

In 1964, Greene pursued a doctorate degree in education from the University of Alabama, simultaneously serving as a graduate assistant football coach under the legendary Paul “Bear” Bryant.

Three years later he left with his degree and his life partner, Patricia, his wife of 57 years.

Building A Program

By 1968, the then 39-year-old was hired to spearhead the baseball program at Kendall Campus, then known as Miami-Dade South. He saw the program evolve, from the planting of the outfield trees to the addition of a scoreboard.

“He watched every blade of grass grow,” Patricia said. “He watered that field and he loved it, more than his own lawn.”

Under Greene’s tenure, the Dade-South Jaguars earned state championships in 1970, 1978 and 1981.

They also reached the Junior College Athletic Association World Series twice (1978 and 1981), winning it all in 1981. During his storied career, Greene earned National Junior College Athletic Association Coach of the Year honors and he was inducted into the Junior College World Series Hall of Fame in 1991.

Greene was selected into two other Halls of Fame: the American Baseball Coaches Association (1994) and the Florida College System Activities Association (1995).

Cross-Town Rivalry

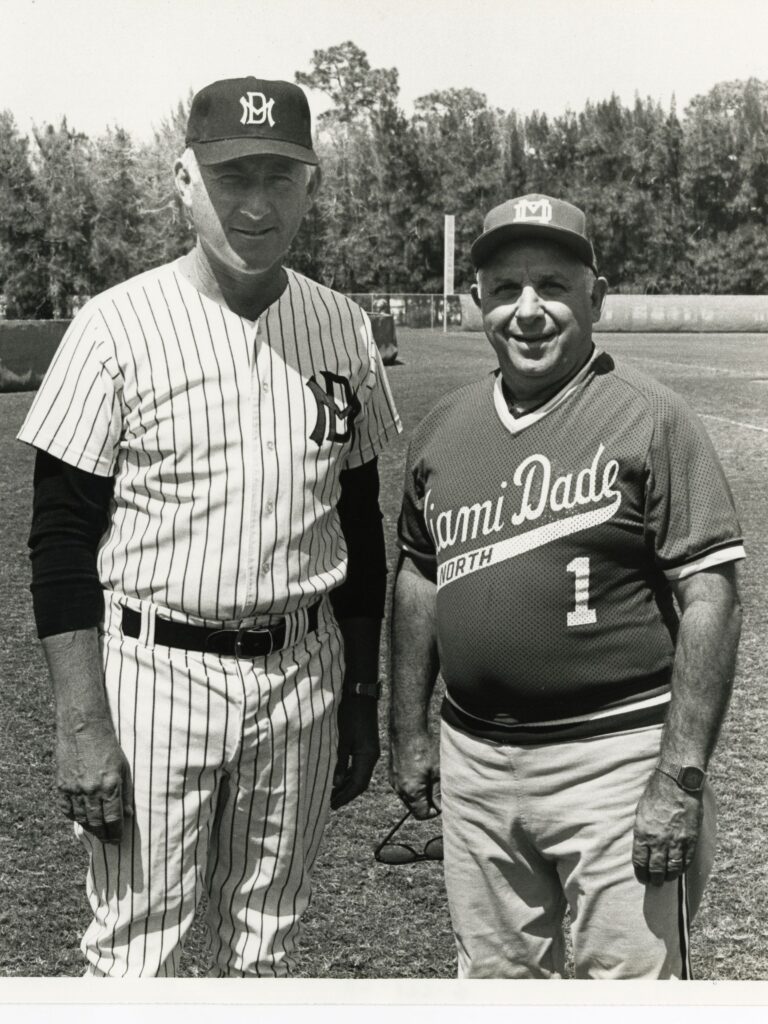

Greene’s biggest battles happened when he faced cross-town rival Demini Mainieri, who started the baseball program at North Campus in 1960.

Mainieri, who retired with 1,012 wins, and Greene, who finished with 935 victories, were neck-and-neck for more than two decades.

Sharks catching coach Rudy Arias, who played for the Dade-South Jaguars from 1975-77, recalls being caught in the middle of the feud.

As a sophomore, the catcher was hit in the back with a pitch during a game at Dade-North. Greene stepped in to prevent tensions from escalating.

But despite Greene’s attempts to keep the peace, “all hell broke loose.” Greene never let Arias live the scuffle down.

“‘Rudy, you started the biggest brawl,’” Arias recalls Greene saying. “‘Every time he saw me, he would tell the story to everybody.”

Although the competition was fierce, Greene and Mainieri were forever intertwined—ironically, Greene died eleven years to the day of Mainieri’s passing.

“It was like the younger brother with the bigger brother…they had a few friendly disputes, but we were friends,” Patricia said. “On the field, you were very competitive, and then off the field, we went to their house for dinner.”

Devoted Father

While Greene had an ardent commitment to coaching, he alway had time for his sons, Charlie Jr., Michael and Chris. He religiously attended their baseball and basketball games.

“He would come right from his games to our games in full uniform, a lot of times. He wouldn’t even wait to get home to shower,” recalls Charlie Jr., who was a catcher for the Jaguars from 1989-91. “We always knew where dad was—in full uniform in the stands.”

One of Charlie Jr.’s fondest memories with his dad happened during his freshman season. The elder Greene pretended to faint after the youngster hit a home run.

“Everyone thought that was funny, I didn’t think it was funny,” said Charlie Jr., a former major-league player who now serves as Milwaukee Brewers’ bullpen coach. “He didn’t think I could hit a ball that far.”

Greene also served as a father-figure to his players, dedicated to improving their athletic skill and molding their character.

“He was big on… cutting your hair nice so you looked like an athlete, wearing the uniform nicely, tucking in your shirt, wearing your hat right, shining your shoes,” recalls Red Berry, Greene’s best friend who served as a coach at Miami Coral Park Senior High School and at the University of Miami. “And, of course, being on time. If you were a minute late you went home. It didn’t matter who you were.”

Unless you were Alex Fernandez, who went 15-1 for Greene in 1990 and was selected in the first-round of the Major League Baseball draft by the Chicago White Sox.

The talented right-hander, who struggled with being punctual, tested Greene’s patience. One time after Fernandez arrived 10 minutes late to practice, Green was waiting.

“I was a big part of the team,” Fernandez recalls. “He and all the guys [were] sitting in the dugout. I showed up running and he rolled his watch back to make sure that I wasn’t late. He goes to me, ‘You just made it kiddo, you just made it.’”

The hard-nosed coach, who was a stickler for the rules but “never held a grudge,” was also known for holding intense practices. His players were known as “Greene’s Marines.”

Arias recalls fall practices starting at 5 a.m. with laps around the Dade-South track, followed by weight lifting and class.

“He would sit up in the stands and just look at us and we wouldn’t dare stop,” Arias chuckled. “You stop, you were gonna stay there running ‘til whatever time he wanted.”

Despite the tough love, Greene’s players knew he had their best intentions in mind.

“He wanted it done the right way. And he always said this: ‘You’re only as good as what you do when you know no one will ever find out what you did,’” recalls Gil Paterson, who pitched for the Jaguars from 1974-75. “You know, it’s kind of like, [someone] says to you, ‘Go run five sprints,’ but then they leave, and then you only run three. Yeah, well, that’s not what he wanted to build in us. What he built in us was that if no one was watching, we would still do the right thing.”

To this day, Paterson, a pitching coordinator for the Oakland Athletics, carries Greene’s lessons with him.

“Every time I do some of his drills, I think of him. Every time. And I do them every day, for as long as I’m alive,” Paterson said. “I love him and I’m gonna remember him. There’s probably not a day that I don’t think of him.”

Lifelong Passion

There were no days off for Greene when it came to baseball.

He spent summers coaching in the Cape Cod League—a collegiate summer baseball league—teaching minor league players in the New York Mets and the Chicago Cubs system, and helping with the United States national baseball team (Team USA), where he served as head coach from 1988-89.

Greene taught baseball clinics in Germany, Poland, France, Taiwan and Aruba and published several books.

He was the editor of Gold Glove Baseball, was featured in the The Baseball Coaching Bible, and co-authored Build A Winning Pitcher-Catcher Combination. He also wrote monthly articles for Collegiate Baseball, a newspaper that recently shut down.

“He loved baseball,” Charlie Jr. said.

Despite having a pacemaker and undergoing two hip replacements, Greene stayed active until his final days.

He was a member of the Miami Baseball Forum. The group, which has approximately 40-50 members, meets on the first Wednesday of every month at Duffy’s Sports Grill to discuss baseball.

“We would sit next to each other at the Miami Baseball Forum and we would always be at each other’s throats. If somebody came to a forum and heard us go at it, they would think we hated each other, but it was really love. We really loved each other,” Berry said. “We’ll always keep his chair empty in his honor.”

Greene is survived by his wife Patricia, 81, his three sons, four grandchildren—Patrick, Gavin, Shannon and Garrett (a quarterback at West Virginia University)—and the hundreds of lives he touched.

“He’s always told his kids and his grandkids [to] follow their passion,” Charlie Jr. said. “He knew he was never going to become rich being a coach, but he was rich in relationships.”

Click here to subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter, The Hammerhead. For news tips, contact us at mdc.thereporter@gmail.com.